Coronal Holes Explained

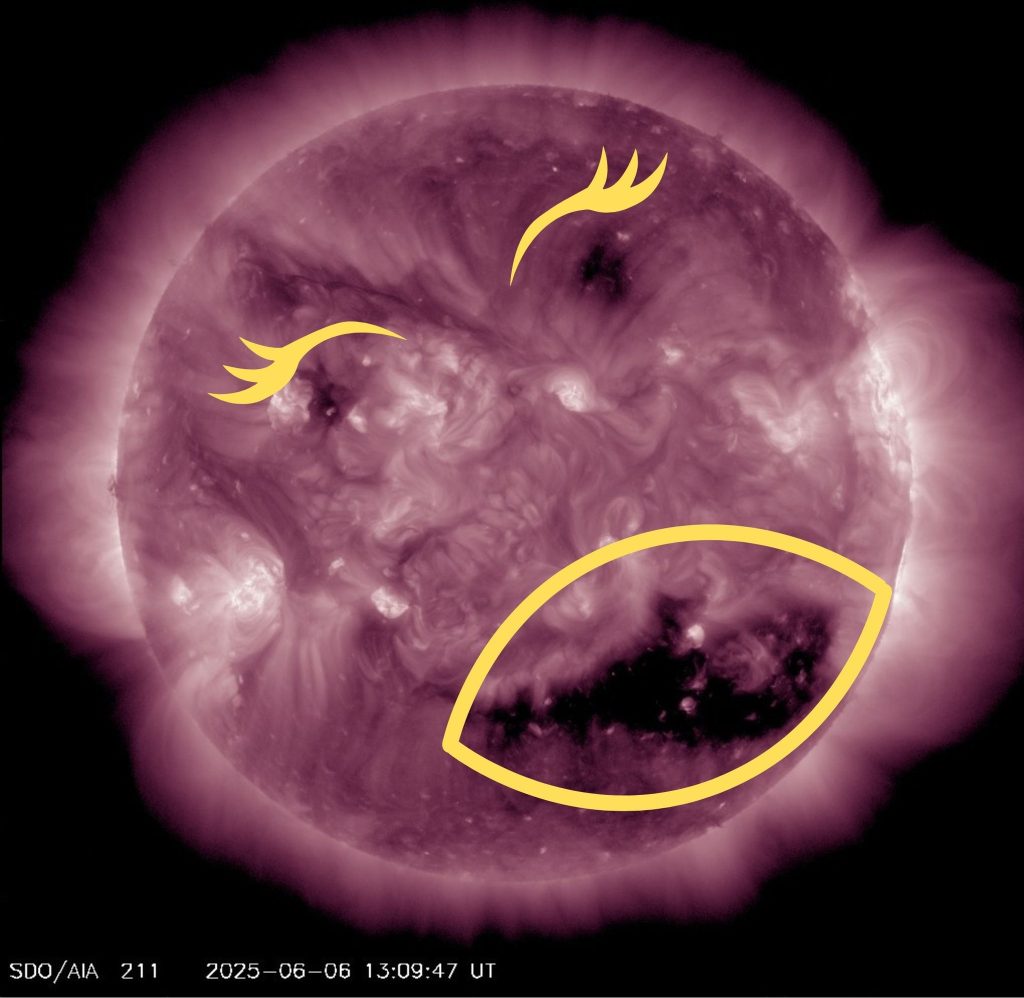

Picture the Sun as a gigantic, overstuffed burrito, bubbling with hot plasma filling and wrapped in a spicy magnetic tortilla. Normally, this wrap holds everything in nicely. But sometimes, the outer shell tears open in a few spots—like a tortilla that couldn’t handle the pressure. These rips are what scientists call coronal holes.

In ultraviolet and x-ray photos, these spots show up looking darker. Because they’re cooler, a little emptier, and not as saucy as the rest of the Sun. Think of them like parts of the burrito where the filling didn’t quite reach, and the steam just escapes straight out. These are the places where the magnetic “wrap” unzips, letting the solar wind—the Sun’s spicy hot sauce—shoot out into space.

This sauce doesn’t just dribble. It blasts out in powerful, fast-moving streams, like someone squeezed the bottle way too hard. Space chefs call these bursts High Speed Streams (HSS)—and they’re spicy enough to be noticed across the entire solar kitchen.

Now, these burrito blowouts (coronal holes) can show up anywhere and anytime, but they’re especially common during the Sun’s “nap phase,” known as solar minimum. Some of them are like slow-cooked leftovers—they hang around for weeks, even through several Sun spins (which take about 27 days each). Most often, these holes camp out near the Sun’s north and south poles.

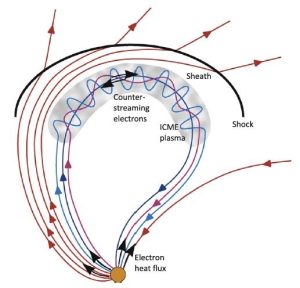

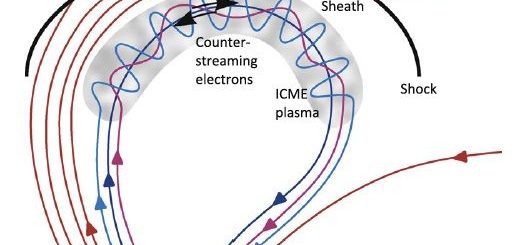

These long-lasting coronal holes are like industrial sauce dispensers—they keep blasting out high-speed solar wind. And when this fast solar salsa hits the slower, lazier background solar breeze floating around out there? It results in a cosmic food fight.

This mess creates a pressure-cooker zone called a CIR (Co-rotating Interaction Region)—basically, where spicy solar sauce crashes into lukewarm space soup. From the sidelines (like Earth), we see the CIR show up first—bringing a sudden burst of density and magnetic strength—like the smell of chili hitting your nose before the taste hits your tongue.

When the real high-speed sauce (CH HSS – Coronal Hole High Speed Stream) arrives, Earth starts to feel the heat. The solar wind gets faster, the temperature rises, and the density starts to thin out. It’s like going from a thick gravy to a fiery consommé. Over time, the spiciness (a.k.a. magnetic field strength) starts to mellow out, just like a curry cooling off after being reheated too many times.

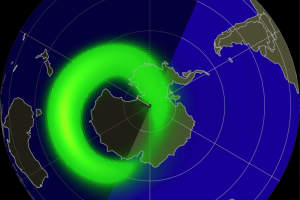

Coronal holes near the Sun’s equator are the most likely to blast their spicy streams straight at Earth. If the CIR is strong and the HSS is supercharged, Earth’s magnetic field gets shaken up—causing geomagnetic storms. These can range from mild salsa-level (G1) to mid-range jalapeño (G2), with the rare ghost pepper moment (stronger storms) when things really get wild.

The larger and messier the coronal hole, the longer Earth stays in the spicy splash zone—sometimes getting splattered for days on end.

So, who wants a burrito now?